Through the Cactus

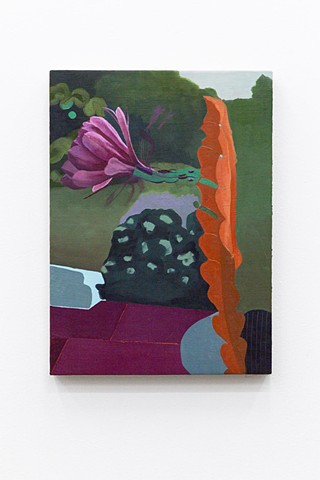

I have been immersed in Nepantla, Mexico for about eight weeks now. Without a doubt, this region—the birthplace of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, 17th century writer and poet who is now considered a feminist icon—is a different context from my usual one in Mexico City. Time here is of a different nature. When I scrub my clothes on the washboard, I think of everything and nothing; I see a little piece of pink Zote* soap on the blue-grayish surface. I consider painting it, but I tell myself that it is surely a bad idea and I keep scrubbing.

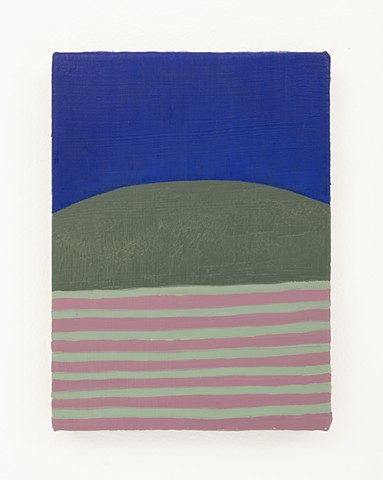

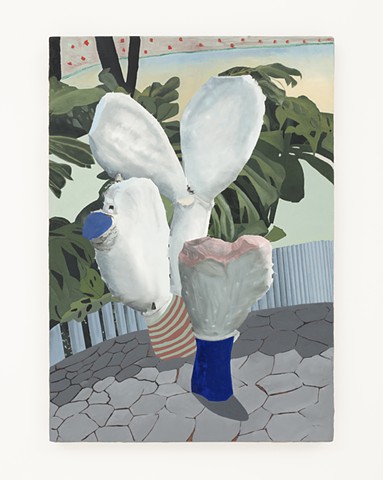

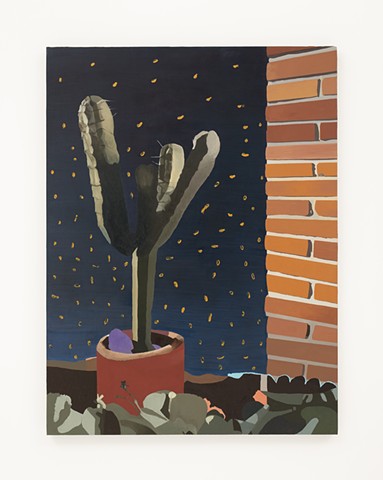

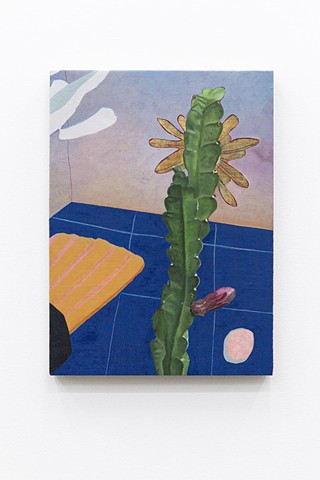

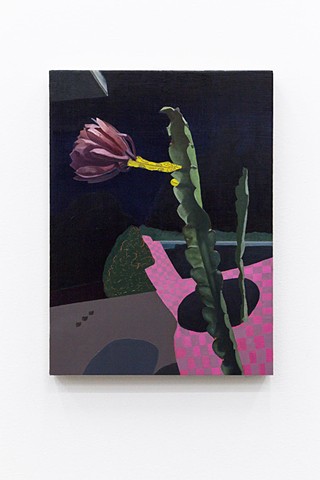

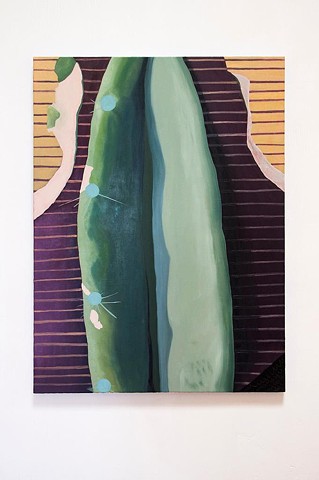

I let go of the thought of painting the soap bar, but now I reflect on the cacti that surround me. The plant life here is very rich and full of round, irregular shapes, calling to mind the biomorphic forms that began to appear in my work prior to this collective interlude. The succulents become more seductive every day and I succumb to the desire to portray them.

I embrace my newfound subject matter, approaching the current interruption as an opportunity to find poetry in what is most banal; to reimagine both the artistic and the quotidian endeavor; to reclaim vulnerability’s ability to drive artistic creation and critical thought.

Perhaps after the cacti I will return to the idea of the Zote soap….

June 2020

*Zote is a Mexican brand of laundry soap popular for hand washing clothes.

Six months ago I began painting cacti because I felt the urge to—I was drawn to their forms and colors, their humanlike presence. Four months after I started depicting Zote soaps as well. The rest came later.

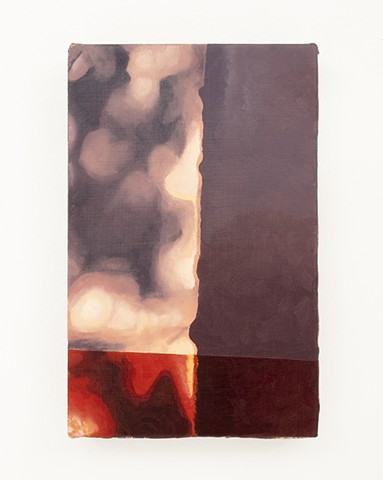

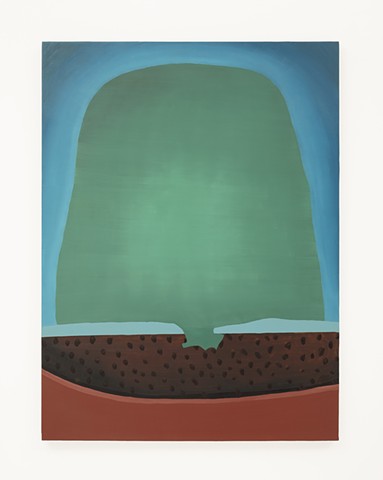

One day I carried my first cacti pieces out of the studio and walked the grounds in search of a place where I could lean them on—I wanted to examine their colors under natural light. What are the implications of taking the painted cacti back into the landscape where they come from? I found a rock that looked suitable enough and rested one of the canvases on it. After this fortunate accident I began to question notions of support—not only structural, but also symbolic, theoretical, social and systemic. In other words: what needs to be there so another situation can take place? And if the reading of an object is always dependent on its foundation, how are new meanings created when it is placed on a different base or in a different site, context or network?

I brought the rock back into my workspace and contemplated the relationship between it and the painted canvas—which lead to a more ample rumination on what constitutes the space of painting. That marked the beginning of a to-and-fro between the studio and the exterior terrain, between what occurs within the pictorial frame and that what takes place outside of it, between what supports and what is supported, between objects and subjects. The paintings opened up to absorb distinct elements and navigate diverse spaces.

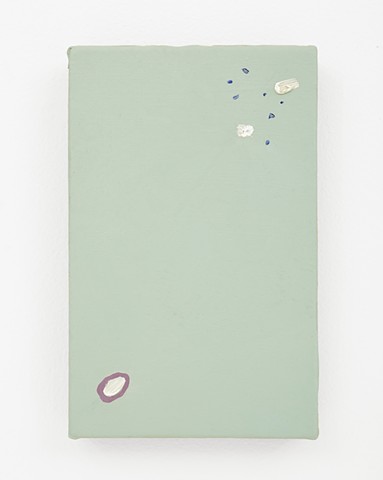

In my spatial reconfigurations natural and manmade items such as rocks and bricks not only dialogue with the paintings—and even with the history of the medium itself—, but are reorder in reaction to a specific place and moment and may or may not result in a finished work. The formal and discursive possibilities are varied. The painting is propped up by a set of rocks—mineral found objects which coexist with the cacti in the natural environment—or in the inverse, small pebbles are placed on the top edge of the canvas. In some instances bricks support the rocks—the architectural underlie becomes a pedestal for the rock which acts as the symbolic landscape. In other occasions the surfaces of bricks are also painted as a grid or as a monochrome, pointing to key gestures in the history of painting and probing into the nature of the pictorial frame. What is the difference between the painted canvas and the painted brick? In the end they are both rectangular supports that present a flat surface. Material and historical hierarchies are broken.

Yet, it was the drive to render the regal yet gawky shapes of the succulents and to mix the enticing pink hue of the soaps on my palette table—in order to understand how they related to my own abstract language—that lead me to reconsider the function and relationship of these elements—the cacti and soaps, but also the paintings, rocks and bricks—, as well as the spaces they occupy: the studio and exhibition space, the natural environment and our domestic habitations. It is through painting—and through the cactus—that I am able to navigate the in-between, find interconnections and shift frameworks. Painting is after all a practice of negotiation.

December 2020

*The name of this body of work is inspired by the title of Judy Chicago’s 1975 book: Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist.